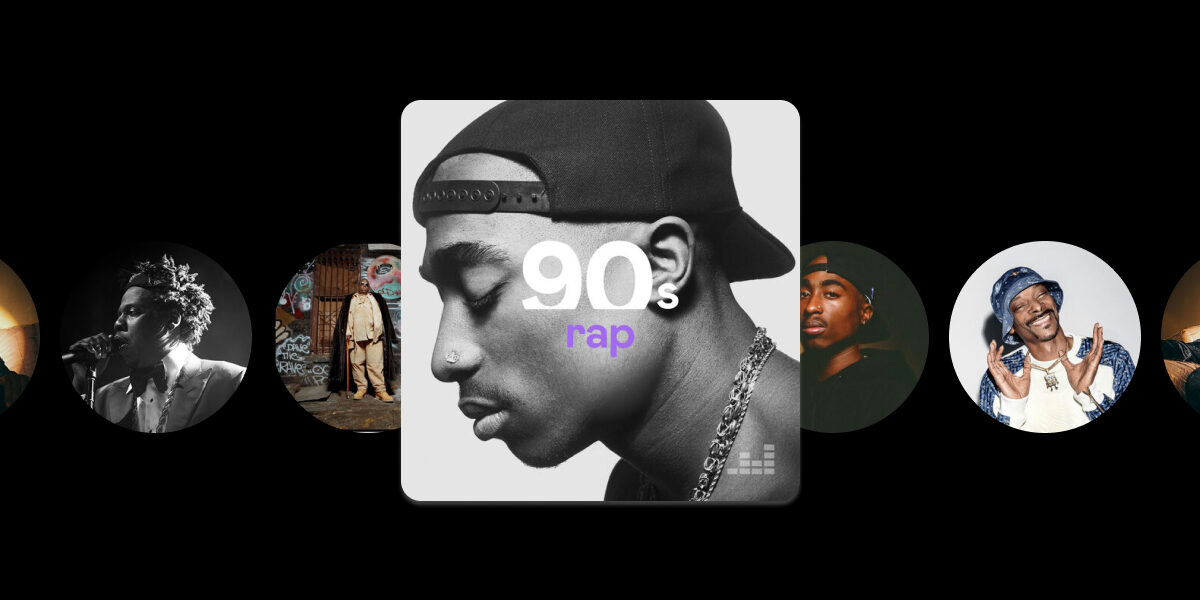

More than just an iconic time for hip-hop, the mid-’80s to the mid-’90s saw underground culture, fashion, and Afrocentric social issues take a step into the limelight. With artists like Dr. Dre, Eminem, and 2Pac each selling tens of millions of albums, rap music became a lifestyle for many, a new way of looking at the world that revolutionized youth culture with memorable beats and lyrics.

A golden age of top lyricism, flashy fashion, and social reckoning

The golden age of hip-hop was sandwiched between the old-school hip-hop era (1979-1983) — with its funk and disco influences, plus the iconic ’80s hip-hop song “The Message” by Grandmaster Flash and The Furious Five (1982) — and the “jiggy” era of the late ’90s, known for its upbeat instrumentals and sampling of ’80s hits.

When you hear “golden age,” think hip-hop artists like LL Cool J, N.W.A., Eric B. & Rakim, Nas, Public Enemy, and the Beastie Boys. But also think DJing, breakdancing, graffiti, rap battles, sneaker culture, sampling, gold chains, knuckle-duster rings, and doorknocker earrings. This age was a time of bold socio-cultural statements and questioning authority and norms.

Public Enemy is a perfect example of just how tight the relationship between music and culture became during this time. Their song “By the Time I Get to Arizona” (1991) exemplifies revolutionary hip-hop with cutting lyrics and sonically bold backdrops. It speaks of their frustration with the state of Arizona refusing to make Martin Luther King’s birthday a holiday. The song was popular enough to affect the state’s tourism revenue in a major way, ultimately contributing to Dr. King’s birthday becoming a national holiday the following year.

Public Enemy’s music, inspired by Run-DMC’s urban sounds, also crossed over into the film world. One of their most important songs, “Fight the Power” (1989), was initially conceived as part of the soundtrack for Do the Right Thing, director Spike Lee’s provocative film illustrating a day in the life of Black youth in Brooklyn. As the track’s title suggests, PE’s music is a shout for justice and corrective action — and became a blueprint for future political hip-hop, like Kendrick Lamar’s single “Alright” (2015).

Hip-hop artists who left a mark

NYC was the golden age’s main backdrop and the stomping ground for artists like Big Daddy Kane, KRS-One, Rakim, Chuck D, LL Cool J, the Beastie Boys, De La Soul, Nas, 2Pac, the Notorious B.I.G., Jay-Z, and Run-DMC. It was a place of intense competition, where stylistic differentiation, creative sampling, and lyrical mastery were essential for rappers to stand out.

Take Rakim, for example. As part of the MC/DJ collective Eric B. & Rakim, he was (and continues to be) considered one of the most technically skilled lyricists in the hip-hop industry. Aggressive when attacking every line, Rakim – admired by Nas and Eminem – provided a great example of intellectual and cultural wit through albums like Paid In Full (1987), Follow The Leader (1988), and Let The Rhythm Hit ‘Em (1990).

A gifted lyricist and a six-packed charmer, LL Cool J stepped into the spotlight at age 16 through Def Jam Recordings (which, to this day, is recognized as one of the most important record labels in hip-hop history). With perseverance, skill, and charisma, LL built a solid, time-spanning career that also included film roles. Two of the artist’s finest music releases are Mama Said Knock You Out (1990) and Mr. Smith (1995), which include referential hip-hop classics still popular today.

’80s hip-hop born on the East Coast was becoming a staple of radio channels as the decade was coming to a close — and on the West Coast, a new subgenre was taking shape. Although the music style and the location were fresh elements, the lyrical concerns and socio-political frustrations stayed the same across geographies. It was time for gangsta rap.

Gangsta rap music was born in Compton, a small city south of LA, and it came to life through the five-man collective N.W.A. As an outlet for airing out life’s daily struggles, gangsta rap disrespected women and glorified guns, crime, and drugs, all while often touching on topics like police brutality and racial profiling. N.W.A., calling themselves “the world’s most dangerous group,” released their debut album Straight Outta Compton (1988) to great public response: it became the first hip-hop album to win a platinum certification, with one million copies sold at the time. In 2016, the album became the first rap album inducted into the Grammy Hall of Fame.

Post-N.W.A., two of its members, Ice Cube and performer-producer Dr. Dre, found individual fame. Ice Cube’s funky-bass ’90s hip-hop songs featured on his debut solo album AmeriKKKa’s Most Wanted and later, on his Death Certificate and Predator albums, stood out for the sharp social commentary and offensive language. Although often criticized for the latter, Ice Cube became one of the most respected MCs (masters of ceremonies) in hip-hop.

Dr. Dre, still considered one of the greatest hip-hop performers and producers of all time, released his solo debut studio album, The Chronic, in 1992. Winning a Grammy Award for Best Rap Solo Performance for the single “Let Me Ride,” Dr. Dre was also a co-founder and co-president of the well-known label Death Row Records and managed and produced for some of the greatest hip-hop artists of the ‘90s and 2000s, including 2Pac, Eminem, Snoop Dogg, and 50 Cent. The Doctor helped create and popularize the West Coast G-Funk, a subgenre of hip-hop that features synthesizers and slow, heavy beats.

The legacy of the golden age of hip-hop

Many say that the end of the golden age of hip-hop came in the late 90s with the sudden deaths of two of the greatest in the industry: Tupac Shakur (2Pac) and the Notorious B.I.G. The two rappers — along with an expansive roster of talented performers, MCs, and producers — made the golden age a remarkable period in hip-hop music. Fearlessly bold, highly innovative, and aggressively competitive, the golden age artists created sounds dictated by their everyday experiences, communities, and inner struggles. Less influenced by big labels and music industry precedents, these artists dared to use their sounds and lyrics as powerful social and political tools, opening the doors for current-day artists to dare to say what they want to say — and change the world in the process.

To read on the same subject: